Jacques Plante, Clyde Duncan And A Perplexing Dream

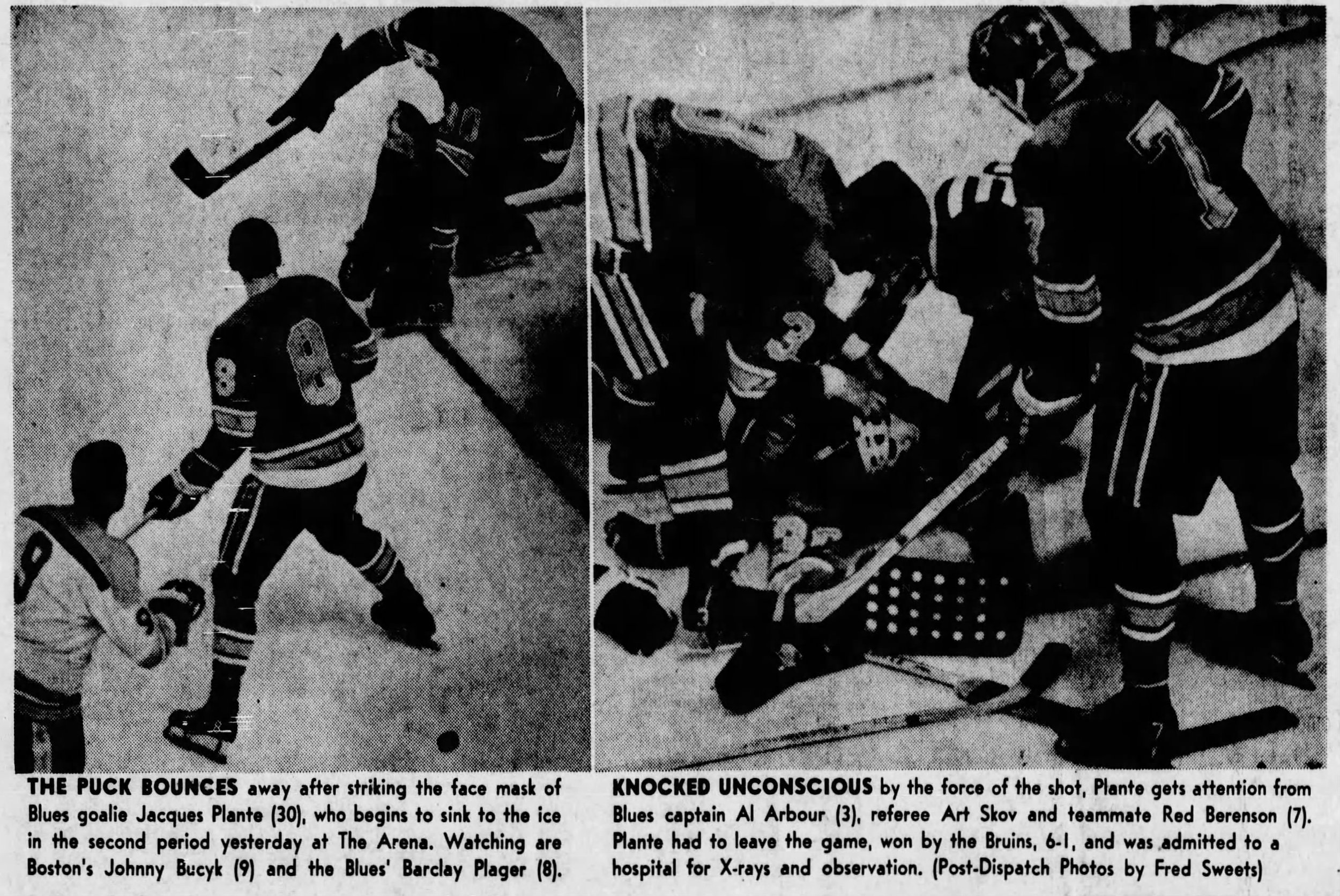

Photos and cutlines from the May 4, 1970 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, after the Blues lost 6-1 to Boston in Game 1 of the Stanley Cup Finals, and lost Jacques Plante to Fred Stanfield’s blistering shot.

According to the Sleep Foundation website, “Dreams are one of the most fascinating and mystifying aspects of sleep. Since Sigmund Freud helped draw attention to the potential importance of dreams in the late 19th century, considerable research has worked to unravel both the neuroscience and psychology of dreams.”

That said, the foundation acknowledges the “neuroscience” remains unresolved. The fundamentals of dreaming, i.e why we do it and what dreams mean, is unexplained.

One might point out there are exceptions, dreaming incidents that are not so perplexing. For instance, Game 1 of the 1970 Stanley Cup Finals is a good example. On that occasion, Blues goaltender Jacques Plante began dreaming early in the second period, and the neuroscience behind it was obvious.

Plante had reached a deep stage of REM sleep as a direct result of a slap shot by Boston center Fred Stanfield.

For background, Stanfield had a terrific NHL career that included 211 goals, 616 points and two Stanley Cup rings. What’s more, he scored 27 goals while playing 61 games with the Central Hockey League St. Louis Braves during the mid 1960s.

“Fritz” had what is known as a “heavy” shot. The hard rubber disc arrived from his stick like a left hook from Sonny Liston. One of the hardest punchers in boxing history, Liston scored 39 knockouts in 50 professional wins. Had the Sleep Foundation been around in the 1960s, Liston would have been highly regarded as an advocate and reliable source of research subjects.

As for Plante, the 41-year old netminder was guarding the basket for the Blues in the second period of that 1-1 game when Stanfield launched. Re-directed by the stick of Phil Esposito - another former Brave - the missile struck Plante just above the left eye.

Fortunately, he was wearing a protective mask. Unfortunately, equipment technology wasn’t quite what it is today. A 1970 goalie mask offered only slightly better protection than a mud mask at the local salon.

Thus, Plante went to sleep- immediately - and remained unconscious for about two minutes. You didn’t need Freud to explain the neuroscience involved. There was a cuckoo clock, stars of various sizes circling his head and Brahms Lullaby playing in the background.

By the grace of God, Plante left the ice on a stretcher not in a box. But it was his last appearance for the Blues and the last appearance of his mask, which was cracked by the force of the shot.

The point being, that particular dream situation required no psychological study.

But most dreams are hard to explain, both why they happen and what they mean. Sleep Foundation studies show most dreams are like Clyde Duncan’s career with the Football Cardinals, hard to explain and impossible to remember.

But occasionally dreams stick, residue from a jolting nightmare or a whimsical adventure. And sometimes, the science in the neuros leaves us searching for significance.

And that's the kind of dream I had the other night.

In the dream, the Ol’ Bogeyman was back on the beat, corresponding from a PGA Championship at Valhalla Golf Club. Nothing unusual, been there, covered that.

But in the Media Center alongside was my father and my brother Tim.

Laurence J. O’Neill Jr., passed away in September, 1990. He was known to his nine kids and most of their associates, as the “Skipper,” in deference to his preoccupation with baseball. It wasn’t just a game to my dad, it was a language, a philosophy, a theology … Most of life’s most challenging aspects could be explained in balls and strikes, most of its rewards were contained in a boxscore.

Moreover, my dad was a lifelong St. Louisan who loved the game and despised the hometown product. He derisively referred to the Cardinals as “The Budweisers,” holding them somewhat responsible for the departure of his beloved American League Browns. He loved New York, but no self-respecting Browns fan could show allegiance to the Yankees.

When the Mets came along in 1962, featuring the kind of captivating characters and hapless properties that defined the Browns, he adopted the “Lovable Losers.”

On that night in 1990, the phone rang in the Busch Stadium press box. I was working on a Tom Herr profile; the former Cardinal was back in town as a member of the Mets. The call was from the hospital, concerning the “Skipper,” and the message was clear - "hurry."

But I was in a major league press box, covering my dad’s team, explaining how the hero of 1987’s “Seat Cushion Night," had crossed over. I wanted the Skipper to open the paper the next morning. so he would call first thing, as he did with every byline I had. I put down the phone and finished the story.

When I got to the hospital he was gone, never got to talk about Herr, never got to say goodbye.

Many years later, April, 2021, the phone rang at my house. It was from a hospital and it concerned Tim. His heart was failing.

Tim and I were a year apart. As kids we shared everything - friends, float trips, paper stands, pinball, mischief and mayhem.

Tim was a remarkable combination of no-sense morality and pure nonsense mirth. For instance, when The Exorcist hit theaters in 1973, it caused quite a stir, long lines at box offices, people fainting in their seats, prayer beads flying off the shelves.

The film was particularly upsetting to Catholics, hitting us in the demonic sweet spot.

I went to see the late show one night with a friend. When I got home, still somewhat rattled, I went straight upstairs. The lights were off, the bedroom was still, all was calm, all was bright. I climbed into the top bunk, closed my eyes, made the sign of the cross and tried to think happy thoughts.

After a few minutes, just as I was nodding off, a loud banging erupted on the bed frame, followed by a shake, followed by a long guttural scream: “Regan! … Regan!” Even a Sleep Foundation neuroscientist would have lost it.

I jumped up in bed and almost hit the ceiling. Then came the laugh from the bunk below. He had stayed up half the night, feigned sleep and waited for just the right moment … to scare the living crap out of me. That was Tim.

That April night, as I raced to the hospital, I was scared again. I arrived to join Tim’s kids and my brother Terry in the waiting room. In the middle of Covid culture, we weren’t allowed anywhere else. At one point, a doctor emerged to say he was stabilized, then came another relapse. As the night wore on, they promised to keep us updated. I took a moment to use the restroom

When I came back, the waiting room was choked with grief. He was gone, never got to reminisce, never got to say goodbye.

Now, here was the dream and there they were, in the most unlikely of places. My dad considered golf a waste of time and I don’t recall Tim ever swinging a club - not counting the time we went slug-hunting with a 5-iron.

What made the dream even harder to understand was, while they were there, they never spoke to me. My dad talked to Tim - probably asked where they kept the Pepsi - but neither of them spoke to me.

I’m sure Tim had something snarky to say. I wondered what dad thought of the Herr piece. But never a word.

What does it mean?

To be honest, I don’t care. I was just so happy to see them.